Whenever I play a new deck-building roguelike I go through the same 3 phases: discovery, refinement, and boredom. Initially, the game in question has so much mechanical depth to unfurl as I uncover different card types, and how they interact with one another. This is followed swiftly by refining that mental catalogue of cards to optimize for the most consistent strategies, and eventually growing bored once I feel like I’ve mastered the game. Generally, I struggle to maintain interest in a title when there are no worthwhile challenges to overcome.

However, this eventual mastery of roguelike deck-building feels somewhat antithetical. A core tenet of roguelike design is the inclusion of randomness. The framework of the game is the same each time you play it, but the powers you find, enemies you fight, or even the level layouts can change. As it relates to deck-building, roguelikes tend to shuffle which types of cards, and which card modifiers a player will find every time they play the game. This should prevent players from forming perfect strategies. They may know which cards work best together, but they’re never guaranteed to find them thanks to the game’s roguelike structure. Instead, strategies need to be crafted on the fly, similar to how draft formats work in collectible card games.

For those unfamiliar, the draft format is one where players need to construct the best possible deck from a series of random card pulls before they begin playing. You aren’t aware of the contents of future pulls, so part of the strategy comes from choosing flexible cards until you can narrow in on a particular set of mechanics. It’s fun entirely because players can’t construct perfectly balanced strategies. Instead, they have to work with the randomness, which can lead to unconventional card combinations, and thrilling victories.

So how is it that players can master, and eventually grow bored of a game when they’re always given random cards? Shouldn’t each time they play be full of boundless opportunities for new, and exciting card combinations?

Yes.

However, in my experience that’s rarely been the case. That was until I played Balatro. It’s a game designed in such a way where I simply can’t optimize it. In fact, it’s the first deck-builder in forever where I’ve gotten that same feeling I do while playing draft mode in other card games. And I love it for that.

Before we can get into how Balatro prevents players from optimizing it to death, let’s briefly touch on how it’s played. I promise this explanation will be relevant later.

Each game of Balatro starts out with a standard set of French playing cards. For those unfamiliar, that’s 13 numbered cards from 1 to 10, and 3 face cards with pictures of a Jack, Queen, and King. There are 4 copies of each of these card types with a different colour, and symbol on them. This is known as a suit. With our 13 card types, and 4 suit types that brings us to a grand total of 52 cards in our standard French deck.

The deck is then shuffled, and the player is dealt 8 cards. They can play or discard up to 5 of them at a time. The goal is to play the best possible Poker hand, or hands that the player can cobble together. Every played hand is scored, and if the player manages to surpass a certain scoring threshold they win and move onto the next round. It should be noted that your score is cumulative, so playing multiple different hands is also a viable win condition. The only stipulation is that you need to surpass the score threshold within 4 played hands.

It should also be noted that the base scoring for each hand type is proportional to how rare it is to draw. The hierarchy of Poker hand types takes into account how statistically unlikely each hand type is, and Balatro uses this as part of its scoring system. For example, a 4 of a Kind (drawing all 4 copies of a particular card type) is much rarer than a Flush (having 5 cards from the same suit). As such, playing a 4 of a Kind will award more points than a Flush.

Knowing all of this, you might be inclined to assume that Balatro is simply a game of numbers. The deck starts with an identical composition every time, so players can discard cards until they’ve assembled one of the rarer hand types, play it, score a bajingus points, and win. The game is already solved, and we haven’t even started playing it. Easy peasy.

In a sense that’s correct, but in actuality Balatro is rarely that straight forward. The default scoring modifiers for even the rarest Poker hands won’t carry you far beyond the second of 8 bosses. That’s where we get into Balatro’s other mechanics.

The first of those aforementioned mechanics are consumable items that players can buy in Balatro’s in-game shop. The first and most obviously useful are Planet cards. These increase the score and modifier for a particular hand type. This makes keeping up with Balatro’s ever increasing score thresholds substantially easier, and also increases the value of scoring specific Poker hands.

The other types of consumables are Tarot and Spectral cards. Both of these will cause a variety of different effects to be applied to the playing cards within your deck. The main difference is that the more common Tarot cards tend only to apply to 1 or 2 cards, whereas rarer Spectral cards can augment up to 10 of your deck’s cards at a time. The types of effects these consumables have include, but aren’t limited to: duplicating existing cards, changing the suit of several cards, removing cards, and applying special bonuses like increasing a card’s value when it is being scored.

You can also buy booster packs to stock up on additional copies of a particular card that you’re building your entire strategy around. Want to consistently pull off a 4 of a kind hand? Why not stack your deck with 12 copies of a given card? That’ll surely make it easier to line up that high value 4 of a kind with substantially less friction.

There’s also Balatro’s answer to what are commonly referred to as relics in other roguelikes: Jokers. These are items that provide some kind of passive bonus. For example, one Joker increases the default scoring modifier by 4. Another increases your base score value by 30 for every odd numbered card that is being played. Yet another increases the total modifier level by a factor of 3 if you’ve already scored the hand type that you’re playing in the current round. These bonuses don’t tend to be super impactful on their own, but when they’re combined they really start to add up.

And it’s here, at the intersection of all of these bits and bobs, that we finally see why Balatro is so difficult to master, which makes every run feel unique. There are so many different combinations of cards, consumables, and Jokers that the player may find while playing the game. In addition, your starting point is always a standard French playing card deck, so there’s no one strategy that is immediately better than another. In essence, the volume of randomness makes it impossible to chart a consistent strategic path, but the flexibility of your starting position gives you limitless directions to branch out into. Balatro’s very design facilitates heterogeneous deck-building in the exact same way that the draft format does for other card games.

For an example of this in action, we can examine a run where I had the Flash Card Joker. This Joker increased my score modifier by 2 every time I rerolled the contents of the in-game shop between rounds. Rerolling isn’t free, and the amount of money you earn from each round is low enough to limit how often players can feasibly increase Flash Card’s modifier bonus.

However, I also had the To The Moon Joker which effectively doubled the money I earned from each round. This gave me the financial resources to reroll the shop several times, which eventually led to Flash Card providing a flat +200 modifier to every single hand I scored. The sheer power of this combination meant that I could play literally any hand type I was dealt, and would still score an ungodly amount of points for it.

There was also the time I found The Family Joker very early on in another run. This Joker increases your score modifier by a factor of 4 whenever you play a 4 of a kind. I wasn’t able to make immediate use of it, but later on I managed to stuff my deck with 8 copies of the 9, and Jack cards. I also increased the base modifier of 3 of a kind hands by playing several Planet cards. This combination allowed me to somewhat reliably play a 4 of a kind to win a given round, while using a combination of my limited discards, and 3 of a kind hands to help thin out my deck.

In both of these examples, I was forced to utilize the options that Balatro presented to me to the best of my abilities. I wouldn’t have normally pursued a deck built around scoring a 4 of a kind, like I did in my second example, because that hand type is extremely rare. However, the Joker I found was so powerful that I started building my entire strategy around it. That included drafting more copies of specific cards, and even having a back-up plan in case I couldn’t line up that 4 of a kind hand.

Balatro’s very design actively challenges the way I tend to play games in this genre, and has kept me thoroughly entertained as a result. I simply can not optimize this game. Every single run requires that I think on my feet, and take educated gambles to ensure future success. It’s extremely compelling to play, and I love it for that.

Before I cap things off, I’d like to circle back to something I said early about my experience with other roguelike deck-builders. I noted that while these games should play like Balatro – they should have a degree of randomness that asks the player to think on their feet, and make interesting decisions – that’s not really been my experience. Instead, many of them are built in a way where I’ve been able to reliably construct very homogeneous decks, which utilize the same core strategy every single time I play the game.

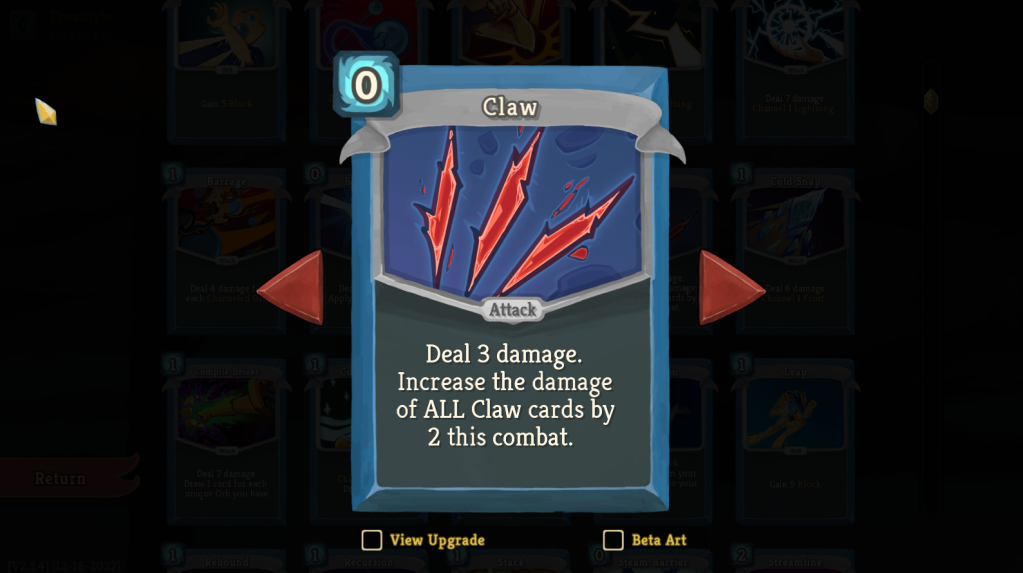

Nowhere is this homogeneous deck problem more apparent than with Slay the Spire, specifically the Defect. This class has a ton of unique cards with loads of mechanical depth. However, every single time I play them, I invariably do so the exact same way. Many of the Defect’s cards don’t have the flexibility to synergize well with one another. When you get lucky and find all the right cards then you can create a really novel deck, but I normally find it easier to simply build around a single common card called Claw.

The Claw card costs no energy to play, and deals a measly 3 damage. However, every single time a Claw card is played, all Claw cards have their attack power increased by 2 damage. This means that Claw can increase in power, quite dramatically, over the course of an entire encounter. It may start doing only 3 damage, but you could be dealing an enormous 30 damage with Claw by the end of a fight.

It isn’t just the high damage potential of Claw that causes me to build around it though.Claw is also a common card. This means that players are very likely to find Claw at least once every single time they play Slay the Spire. Obviously, having more copies of the card increases its usefulness, but I’ve easily won numerous times with only a single Claw in my deck.

It isn’t just Claw that is a common card though: many of the cards that synergize with Claw are also common cards. Rebound, Sweeping Beam, and Hologram all create scenarios where the player can reliably play the same Claw card multiple times in a single turn. For example: you can play Rebound, which puts the next card you play at the top of your draw pile, then play Claw. Follow this with Sweeping Beam which draws 1 card, so you draw the Claw you just placed on top of your draw pile. After playing Claw a second time, it’ll be in your discard pile, but that just lets you play Hologram to pull Claw back into your hand. That’s 3 Claw uses in a single turn culminating in 24 damage from just Claw, and it’s all thanks to cards that will always be given as draft options because they’re common.

Claw would already be a fantastic card if it only had synergies with those previously listed common cards, but it also synergizes excellently with a handful of uncommon, and rare cards. Players aren’t guaranteed to find all of these cards, like they are the common cards, but they’ll definitely find a couple across any given run. And it only takes a couple of these cards to further increase the volume of Claw shenanigans.

It’s thanks largely to the reliability, and ease of building around Claw that I always use it when playing the Defect. It’s simply too easy to make a winning Claw deck, so I’ve completely optimized everything I do on the Defect around Claw.

To be clear, this kind of homogeneous deck-building isn’t just a problem I’ve had with Slay the Spire. I’ve had similar experiences with Monster Train, and Wildfrost. And I think all 3 games are great in their own right. It’s just that Slay the Spire, specifically the Defect, provides the easiest example to articulate what kinds of experiences eventually caused me to move on from playing all 3 of these games.

Those very same experiences are also why Balatro has felt like such a breath of fresh air. It’s a game that fully embraces roguelike randomness, and manages to feel like a proper draft format deck-builder with every run. Any time I play it, I genuinely feel like Balatro will show me some bewildering combination I’ve never seen before. And the thrill of that discovery keeps me coming back for more.

I’ve been hooked on Balatro for a week now, and after reading your post I think I get why. I’ve barely had any experience with rougelikes at all before this game, but after watching someone play for ten minutes, I knew this was for me. I like the mix of different mechanics that mesh together — I can imagine all the planning and balancing that has to go into a game like this to get it right. Add to that all the great style — the hypnotic music and psychedelic look of a lot of the game, the card art, even the sound effects — it all works for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you’re enjoying it. Though I do wish I’d been the 1 to tell you about it, but this post took me a little longer than I originally planned to write.

Also glad you had a positive experience with your first roguelike title. I’ve been telling people for years to just try games in the genre despite many having the same point of…apprehension about it. People don’t want to “lose all their progress”, but the genre tends to play more like your standard multiplayer game instead of a typical single player RPG. You go in, muck around for 15-60 minutes, and do it again. If the game is fun enough then you don’t really think about it like losing your progress, much like how you wouldn’t think about losing your progress when you queue up for another game of . It’s just a matter of actually finding that title that gels with you enough to break that false preconception that dying, and losing your progress is this Earth shattering setback.

Also-also: holy shit I didn’t even talk about the music here, but the fact that it plays the exact same track over the entire game and it never gets boring, or annoying is truly amazing. I don’t know enough about music to actually say why that is, but it really ties everything in Balatro together with a nice bow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

After having put a bunch of time into Balatro (and will be putting far more time in) I tend to agree. I love the randomness factor and that each run is like a brand new challenge. I am in love Balatro at the moment, its just hitting the right spot.

As for the compairson with Slay The Spire, I could never put my finger on why I found it tedious toward the end of my time with it but I think you have nailed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad I convinced you to pick Balatro up prior to its release. I was pretty sure you’d like it, and I’m always glad when I’m right about those things. Not just for my own ego – it’s also nice to know that I didn’t cause you to waste money on something too lol

re: Slay the Spire – the kind of lack of build variety that’s born out of how you can sort of optimize StS isn’t something a lot of people talk about, but it’s something I noticed in my last stint of playing it. I really wanted to play it again, did, and then wasn’t enjoying myself. So I took the opportunity to examine how I was playing to see if I could figure out why I wasn’t having fun. The lack of build variety due to my desire to win over everything else was what I ultimately concluded was the issue. Just didn’t have an opportunity to include that in an article until over a year later because I really didn’t feel like writing, editing, and publishing a hit piece on what is frankly a great game.

LikeLike

This is a great write-up on Balatro! Every time I play I find myself in an “oh shit it’s 3 AM” situation. Totally agree with you that it defies optimization, which I think is part of the fun – you’re always hunting for that run where you get just the right jokers together to REALLY break things wide open. I’m currently working on getting all the stakes beaten so I can unlock the rest of the decks, I think I am on green stake currently? It’s a blast!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was actually going to recommend it to you, but then I saw that you’d ended up picking it up on Steam before I reached out. Glad to know you’re enjoying it (which I figured you would – hence the desire to reach out and recommend it).

LikeLiked by 1 person